If she had to boil it down to one reason, Madeleine Duncan says she chose to study engineering because she wants a career helping Indigenous communities.

“Engineering problems like access to clean drinking water in these areas are very complex, and I don’t think they can be solved without Indigenous engineers onboard,” she says. “I want to be one of them.”

This year, the third-year Geological Engineering student and member of Curve Lake First Nation took another step toward realizing that goal by participating in the STEM Indigenous Academics (STEMInA) Research Experience Program.

STEMInA is an academic support and community building initiative at Queen’s that offers a variety of services to Indigenous undergraduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math disciplines.

One of those services is the Research Experience Program, where students work on a research project of their choosing with a faculty mentor and then present it to the group.

Duncan’s project was about clean drinking water in the First Nations community of Whatì, Northwest Territories. She presented it to the other students in the program and their faculty mentors late in the winter term.

Duncan’s mentor was Stephanie Wright, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, whose research looks at how climate change impacts groundwater in northern communities.

“When permafrost thaws due to global warming, there’s potential for contaminants previously held in the permafrost to be set loose and make their way into a water supply,” says Duncan. “That’s one of the risks for Whatì.”

Her project and presentation provided background about the problem and some of the engineering being done by Wright and others to try to solve it.

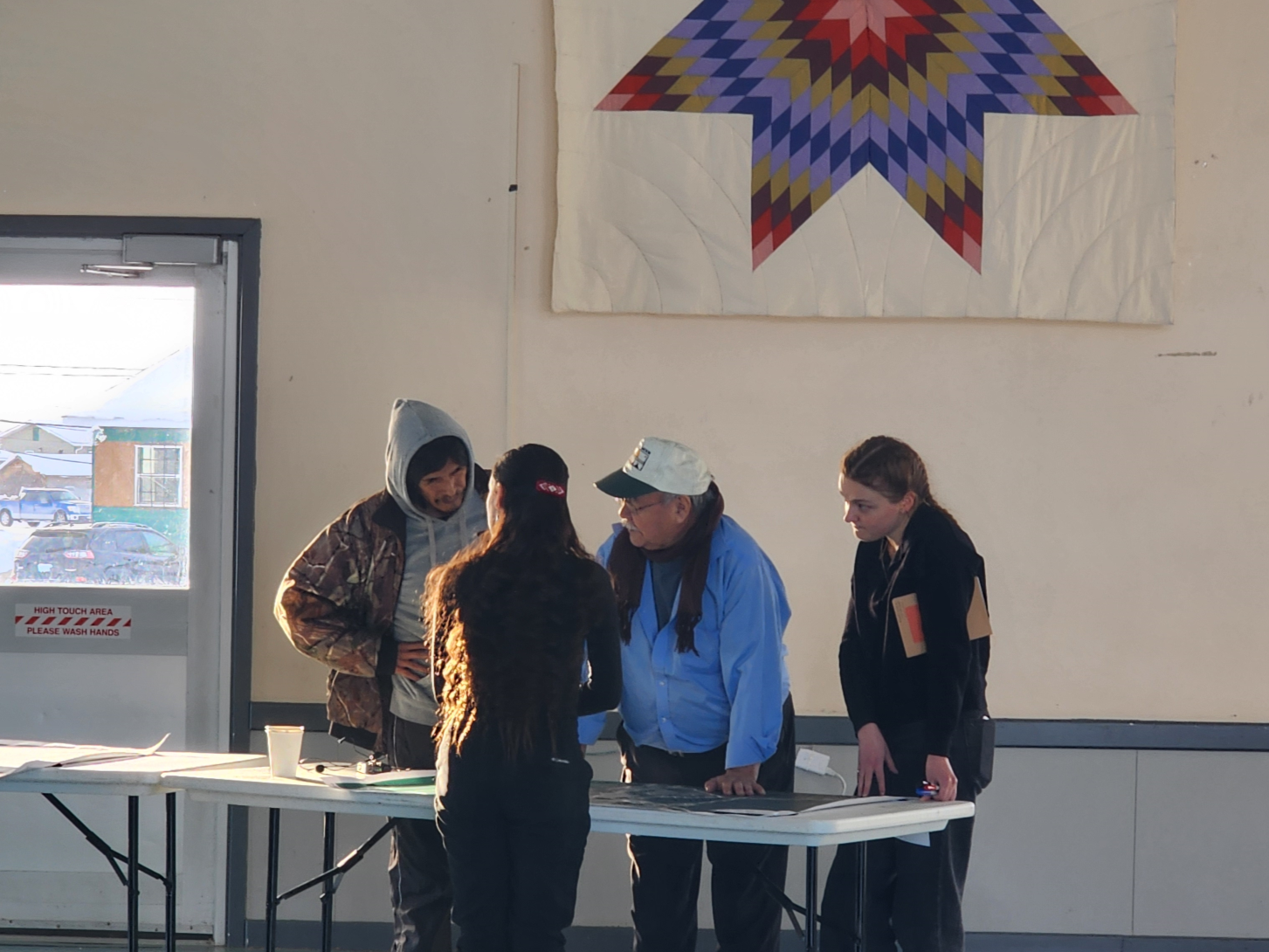

In February, Duncan travelled to Whatì with Wright to participate in a community consultation and a school engagement event. “That was an incredible experience and definitely made the whole project for me,” says Duncan.

One of her biggest takeaways from the trip was the importance of language and communication with Indigenous communities.

In Whatì, about 90 per cent of residents speak Tłı̨chǫ, and not all elders speak English. That can make consultations with the English-speaking engineers challenging, says Duncan. But as she saw, the community has an ingenious way of getting around this: they employ a translator whose Tłı̨chǫ gets transmitted via headsets worn by elders.

Duncan says the trip also opened her eyes to the importance of involving everyone in a community on engineering projects like this one.

“With my school event, for instance, I saw that consultation with youth is going to increase overall community understanding of projects,” she says. “Those students are going to go home and tell their families what they learned, or someday those students will grow up, become the elders, and be the decision-makers in their communities.”

She also thinks that involving Indigenous youth in research and projects like this will encourage them to pursue STEM careers.

It certainly encouraged Duncan.

“I was excited to be involved in a project like this in an Indigenous community because it perfectly aligned with my career goals,” she says. “I’ve really found an interest in groundwater projects because so many Indigenous communities don’t have access to clean drinking water, and it’s a complex issue that’s going to need Indigenous engineers on the team to solve.”

Duncan says she is “so thankful” that STEMInA gave her the opportunity to explore the issue firsthand.

“The reason why I chose to come to Queen’s was because I knew there were supports and programs like this for Indigenous students,” she says. “Whether it’s STEMInA, Indigenous Futures in Engineering, Four Directions, there is a network of support here that has really helped me get through my degree and has really enriched my degree.”