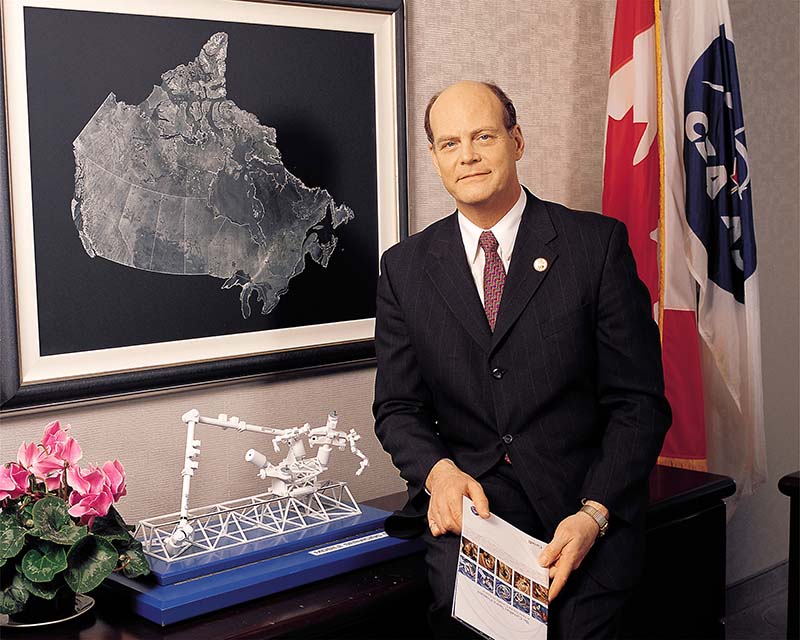

William MacDonald (Mac) Evans has been instrumental in many of the great milestones Canada has achieved in space exploration and research. Not only did he oversee many of Canada’s space projects (e.g. the Astronaut Program, Canada’s participation in the International Space Station, the Radarsat satellites), but his efforts enabled exciting jobs for Canadian researchers, scientists, and astronauts for decades.

In this Q&A, we learn about Mac’s time in the government working on space projects and policy work, and what Queen’s University engineering community looked like in the 1960s.

What is the Canadian Space Agency? What did a typical day look like for you?

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) is a government agency that develops and applies space technology to meet Canadian needs. In addition to providing the robotics systems essential for the construction and operation of the International Space Station, the CSA has world-leading programs in satellite communications, remote sensing satellites that observe the earth to help manage our natural resources and provide situational awareness for civilian and military customers, and space-based science instruments that assist in monitoring climate change.

Before retirement in 2001 I was President of the CSA for seven years. I managed the agency to meet the government’s objectives in space within the budgets allocated to the CSA. As President, I was responsible for advising the government on various aspects of space policy, managing our international relationships with other space-faring nations, and ensuring the development of an internationally competitive space industry in Canada

What was your career path?

My first job was with the Department of National Defence, where I did research on new military communication systems – particularly systems to enhance communications in Canada’s north. When the government approved a new communications satellite to explore the potential for direct to home satellite TV broadcasting (called Hermes) I became manager of the Systems Group, responsible for the overall design of the satellite system. This led to me become the Mission Director for the launch and operation of the satellite in 1976.

Following my work on the Hermes program, I became interested in developing policies and programs for Canada’s future space projects and I moved to the headquarters of the Department of Communications where this work was being done. I was fortunate to work for Dr. John Chapman (the father of the Canadian Space Program) and gained invaluable experience in developing, promoting and obtaining approval for new space policies and programs. It was at this time that I learned the importance of excellent writing skills.

To further my policy development skills, I joined the Ministry of State for Science and Technology, which was a central agency of the government of Canada that focused on science and technology policy development. It was at this time that I prepared the proposal to the government for the creation of the Canadian Space Agency (which the government approved in 1989).

With the creation of the CSA, I became Vice President of Operations, responsible for all major programs of the Agency (Space Station, Astronauts, Radasat). One of the more interesting things I did during this time was to lead the negotiations for Canada’s participation in the International Space Station Program. In this role, I had to develop the tact and diplomatic skills needed to ensure Canada’s interests in the program were achieved as consensus was reached among the partners (Europe, Japan, Canada and the USA) on the structure of the program.

In 1991 I left the CSA to become President and CEO of a company called Precarn, where we led advanced research in robotics and artificial intelligence in partnership with industry and academia. In 1993, the Federal Government invited me to lead the development of a long-term Space Plan for Canada. This Plan, which included $2.7 billion of space program expenditures over 10 years, was approved in 1994 at which time the Government asked me to become President of the CSA to implement the new space plan.

What is your greatest success so far in the industry?

The coolest thing I have done was being Mission Director for the communication satellite Hermes. In that position I got to work with all the different teams involved in designing and building the satellite and learned the project management skills needed to complete a major engineering project.

In terms of my successes, I would say that there are two that I am most proud of. The first was to get the government to agree to create the Canadian Space Agency. Before the Agency was formed, space activities in Canada were managed by several departments. There was no overall Canadian space budget, no co-ordination of activities, and no single place in government where industry and our international partners could access decision makers. The formation of the CSA solved these issues.

The second success that I am most proud of was the development of the Long-term Space Plan in 1993/94. While I was working at Precarn, the new government in 1993 was trying to reduce the Federal deficit and consideration was being given to withdrawing Canada from the International Space Station program. The new Minister of Industry at the time, John Manly, did not think pulling out of the Space Station program was a good decision. He invited me to join his office to develop a Long-term Space Plan that would enable Canada to stay in the Space Station Program and continue with its normal space programs (i.e. Space Science, communications, Earth Observation) within a budget that he thought the government would approve. Our plan was approved by the government in 1994 and guaranteed a robust space program for Canada for more than a decade.

The greatest joy I got out of my career was being an enabler. I’ve had the opportunity to start many programs that have provided Canada with essential space-based services while developing the Canadian space industry capacity and providing good jobs all across the country. It is always thrilling to do things that have never been done before, to be part of a program with high public visibility and support, and to see the inspiration for science and technology that the program has generated in Canadian youth.

How has your time at Queens shaped your career?

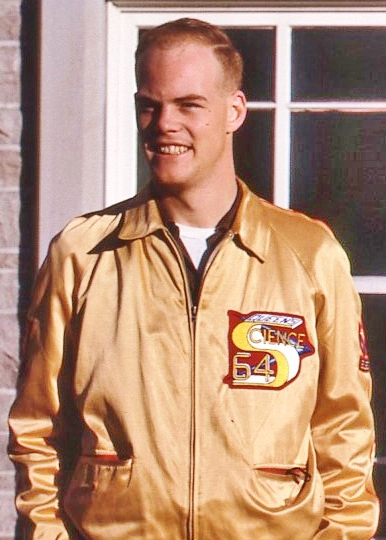

I entered Queen’s in 1960, when it was a considerably smaller place with only 3000 students. We would participate in all the events, and we had a great sense of camaraderie.

I was elected president of my year which made me a member of the Engineering Society. Back then student government was structured so that every year/class had their own president. I was the president of my year all the way through to my third year, and then in my final year, I became President of the Engineering Society which gave me the opportunity to sit on the AMS board. I really enjoyed seeing how student government worked and it gave me insight into the relationship between students and faculty.

When I look back on my studies, the way Queen’s taught engineers in those days gave us a broader understanding of the engineering process rather than making us technical experts in one field. When I compared my education to engineers from different universities, I found that others focused on developing technical prowess, whereas Queen’s focus was on the bigger picture of identifying problems and finding solutions. With my experience in student government, I became more interested in identifying what we are trying to achieve and how best to accomplish the task as opposed to developing the detailed designs that enable us to get there. The Queen’s experience sparked my interest in policy and management work where you set a goal and you work with others to try and reach it.

Fun fact: The Grease Pole was located where Victoria Hall is today.

What did you wish you knew before entering the workforce?

Industry and government work are totally different, and I would say that the skills I developed at Queen’s are more suited to a government job as opposed to the private sector. Not to say that Queen’s graduates are not suited for industry, but I have noticed that Queen’s has been responsible for educating many senior government workers.

Engineering students back in my day had lots of opportunity in terms of job offers. Making the choice of what I wanted to do was difficult, and I did end up choosing government work. Even though I believe I made the right decision, the choice would have been easier if I had known more about what it was like working in industry or government.

How does ethics play a role in your career?

At my first job with the Department of National Defence, my manager made it very clear that if you don’t know something, just say so. Don’t try to pretend that you know something and come up with an answer that is not factual. That was instilled in me at the time, and I’ve carried that throughout my career. The President of the CSA is the most senior space advisor to the Government and it is crucial that whenever I would be talking to someone about my work, I had to be certain that what I was saying was factual and that I knew what I was talking about. When you’re trusted with an important duty, what you say affects your credibility and the projects you work on.

What personal characteristics do you feel are necessary to be a successful engineer/manager?

The best engineers that I have worked with were technically sound, ethical, open-minded, and diplomatic. Not only did they understand the technology needed to solve problems, but they were also leaders that encouraged communication among team members. In policy work these people were tactical, and they understood what it takes to make sure everyone is on the same page. These people were also great writers who could succinctly tell the what, why and how of their proposals to ensure that there were no misunderstandings, or over-statements. These people all understood that their success required diplomatic skills to develop consensus among often competing interests and the ability to develop coherent teams.