India’s information technology industry is the envy of Asia, posting revenues of $190 billion annually and employing four million people directly and another 10 million indirectly. But were it not for a timely offer of a Queen’s University scholarship in 1945, things might have been far different.

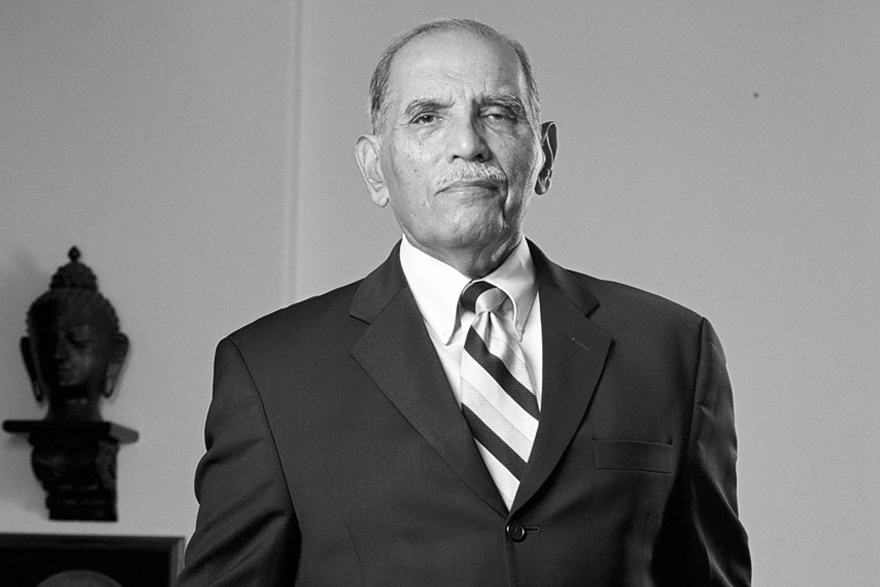

Faqir Chand Kohli – revered as “the father of the Indian software industry” – was a pioneer, a visionary, a titan of business, a champion of social reform and, arguably the key to all the rest, a graduate of Queen’s University.

Mr. Kohli (BSc’48, DSc’07), F.C. to family and friends, died Nov. 26, 2020. He was 96.

Celebrated as “the Henry Ford of IT services” for the way he industrialized the once-boutique production of software, he has also been lauded for his innovations in adult literacy and water purification.

“He firmly believed that the combined power of technology and education could eradicate poverty and enrich India’s enormous human resource,” politician and author Sudheendra Kulkarni wrote in December.

As the founder and first CEO of what was to become one of the world’s largest IT companies, TCS (or Tata Consultancy Services, which is worth more on the open market than IBM), Mr. Kohli realized early the ways in which computers and software would transform the world.

His ability to see such possibilities was unlocked at Queen’s, he told Adjunct Professor Shai Dubey in 2007. Mr. Dubey, who teaches at Queen’s Faculty of Law and Smith School of Business, hosted a dinner for Mr. Kohli upon his return to Kingston to receive an honorary doctorate. Mr. Kohli told him that going to Queen’s “was the pivotal moment in his life. It changed the direction his life was going to go.”

In 1945, Mr. Kohli was at a crossroads. He was in his final year at Government College University, Lahore, in present-day Pakistan, finishing a BA and BSc, when his father died.

“That was a huge blow,” Mr. Kohli told the Indian magazine Seniors Today last year. “Driven by the emotional trauma of my father’s death and the need to be independent, I decided to join the navy.”

While waiting for his commission, he saw a newspaper ad announcing a government scholarship to study electrical engineering at Queen’s. He figured it couldn’t hurt to apply.

“To my surprise, I was awarded the scholarship to study power engineering at one of Canada’s premier institutions,” Mr. Kohli recalled. “The navy agreed to release me from their employment, and I set out for Canada in 1946.”

Mr. Dubey, who himself immigrated to Canada from India with his family in 1967, can imagine the culture shock Mr. Kohli faced. Within Queen’s much smaller post-war student population, “he was a really visible minority,” says Mr. Dubey. “The culture was different; the food was different.”

But more importantly for Mr. Kohli, the educational approach was different, says Mr. Dubey. “The education that he got [at Queen’s] actually helped him to see the world in a different way.”

In India, at the time, education emphasized rote learning, Mr. Kohli told Mr. Dubey. “He said that what [Queen’s] allowed him to do was to think critically. For the first time in his life, he had an opportunity to question. And that was what led to a lot of the other things that happened [in his life].”

It was a turning point. Software for digital “computing machines” was little more than theoretical at the time, but by choosing to continue in electrical engineering, Mr. Kohli set out on the path that would lead to his future innovations.

His BSc from Queen’s earned him a job with Canadian General Electric (now GE Canada), which was focused at the time primarily on the manufacture of small appliances and plastics. The job wouldn’t keep his interest long. Based on his work at Queen’s, he won a scholarship to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned a master’s degree in electrical engineering in 1950.

Meanwhile, his homeland was in turmoil. British India had begun a headlong rush toward independence, resulting in its division in 1947 into two states, the dominions of Hindu-dominated India and Muslim-dominated Pakistan. Millions of religious refugees were displaced in the violence that accompanied partition. Mr. Kohli’s own family had to flee Peshawar for India and start over. With an offer of work from the Tata Group, which operated steel and power plants in India, he returned home in 1951.

Working for the Tata Hydro-Electric Power Supply Company, as it was then called, Mr. Kohli oversaw systems operations for power distribution. In 1968, Tata Hydro-Electric became one of the first companies in the world to use a computer to control the power grid.

Within two years, Mr. Kohli and Tata Group chairman J.R.D. Tata, convinced of the transformative nature of computing, created Tata Consultancy Services to produce operating systems for computers at home and abroad. Mr. Kohli intuited early that western countries would not have the capacity to produce all the software that the burgeoning industry required.

Mr. Kohli and his team “believed they were not building a mere business but a new industry for India,” Subramaniam Ramadorai wrote in his history of Tata Consultancy Services, “and that was a dream worth working towards.”

To realize his dream and produce the talent TCS needed, Mr. Kohli promoted the new Indian Institutes of Technology, created by the country’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Mr. Kohli not only found teaching staff for the new institutes, he taught some of the courses himself.

He continued as CEO of TCS for nearly 30 years, laying the groundwork for the success of both the company and the industry.

“Millions who join the Indian information technology sector every year should celebrate F.C. Kohli, because had it not been for him, the sector would not have reached where it is today,” said Queen’s alumnus Kevin Goheen (BSc’79), in nominating Mr. Kohli for one of the Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science’s 125th Anniversary Engineering Awards in 2018.

And had it not been for Queen’s, where, he told Mr. Dubey, he learned “a way to see the world in a different way, a way not to see the world as it has always been,” his restless mind might never have been unleashed. Even into his 90s and long retired from TCS, Mr. Kohli was still actively pursuing improvements in water purification systems, literacy, and adult education in India.

Mr. Kulkarni, in a memorial to Mr. Kohli, recalls him saying, “Our industry has benefited, but India has not benefited much from our industry. We have to do more, a lot more, for India.”

Faqir Chand Kohli put himself in a position to do just that, thanks to his savvy, his determination – and a serendipitous Queen’s scholarship.

This article originally appeared in the Queen’s Alumni Review.